17. Feb, 2020

There are no secrets to successful leadership - be a humble servant and use your principles to guide

Introduction

Growing up with much rejection, from my birth to the end of my teenage years and witnessing my black peers, adults and children also being repeatedly treated as a subordinate means that it is difficult to welcome success and feel that I have contributed towards something that is successful. As a reflective practitioner being immersed in the living theories methodology, an explanation of my influences ensues in this writing, as I try to live my values as fully as possible and explore how they have been manifested throughout my leadership journey. I have a drive to seek an explanation of my influences, hence it is key that I at least begin to explore what key aspects of my leadership have contributed toward the successful progress and improvement of the schools that I led between 2007 and 2019. What is it that I am doing to engineer the success? In Jack Whitehead’s digital version of the book Living Theories Research as a Way of Life, location 3443 ‘the number of living educational theorists is growing into a global influence on enhancing educational practices and extending and deepening knowledge base of education with individual and community values that carry hope for the mass flourishing of humanity, including our own.’

Through using the living theories methodology reflecting on my values, culture norms, watching complementary YouTube videos, reading and discussing my influences, I begin to reflect on what it is I am doing to engineer success. If identified, then I can repeat and improve the model for the flourishing of humanity, including my own.

The need for me to reconcile the reality of events with the reality of expectations, both mine and others, is strong. I seek to begin to understand why during my leadership in 7 different primary schools I was essentially successful in terms of improving pupil and staff satisfaction and outcomes and inspection by government agents (Office for Standards in Education - Ofsted) or other key outside accountability measures SIAMS (Statutory Inspection of Anglican and Methodist Schools). Even more interesting for me to explore is why after my leadership in the school ended, did the schools return to a failing category in terms of pupil and staff satisfaction and outside agency inspection judgments[PS1] .

In summary, what I have noticed is that my values of justice, equality in opportunity married with a desire to find solutions and feel valued, alongside valuing others have been the drivers behind my leadership success. In this piece of writing I challenge some of my thoughts and share stories of how I challenged myself and challenged and supported the staff to help shift a culture of underperformance to one of sustainable success, so that we could all celebrate being part of a diverse team. On the way I will introduce you to some key players who helped me on my successful journey, helped shift my thinking and who have inspired and helped me to reflect further. [PS2]

The table above seeks to illustrate how the schools progressed under my leadership. 100% of the schools where I was headteacher for 1 year or more were underperforming against most key indicators. These key indicators include, staff absence, pupil mobility, healthy budget, Ofsted or SIAMs or Local Authority or Trust overall judgment, number of pupil applications, pupil attendance, number of complaints, staff engagement, parental engagement, pupil outcomes and standards, quality of education/teaching, improved; staff retention and satisfaction improved and pupil satisfaction and outcomes across all primary phases improved, this was often confirmed by outside agents’ judgements too. However, it is pertinent to note that within 18 months of me leaving the post the climate had changed, results fell, pupils left and staff were leaving significantly quicker than the national average of 15%*. I attempt to explore why the culture of success shifted so quickly after my departure, but focus on what I[PS3] and others, that were influencing me, were doing to shift a culture of failure to one of success.

Reflections

Nelson Mandela ‘I stand here before you not as a prophet, but as a humble servant of you, the people.’

This quote epitomises for me how I felt about the communities I served as a headteacher. I became a headteacher after 19 years as a classroom practitioner. I originally went into teaching because during my education in a rural town in Wiltshire in the 70s and early 80s I had experienced more inept teachers, who seemingly did not enjoy their role or indeed stand before me or any of my peers as our humble servant, than I had of teachers who went above and beyond their job title and did indeed serve their ‘people’. On an altruistic level, I wanted to rebalance the number of inept vs competent teacher and emulate the latter type of practitioner.

As a classroom teacher I had the fortune to work with several talented leaders who had interpreted their role as headteacher as a humble servant of their people. They listened, were patient, considerate and loving toward staff and their wider community, they often had a global perspective and wanted the best for themselves and those around them. As a keen observer I was enormously influenced by them and analysed what behaviours they extoled upon me and others that distilled in us an ambition to be and do even better. They helped staff, children and often parents access opportunities which gave our lives purpose. Often their behaviours recognised our innate value as a human with a voice and talents that deserved to be showcased. We were encouraged to identify solutions to genuine challenges and then use a careful plan to deliver and then reflect on the success or failure and progress of the project. Ultimately our diverse talents were embraced. In Matthew Syed’s 2019 book Rebel Ideas he seeks to demonstrate that by recruiting diverse teams you are more likely to create solutions to complex problems.

‘If we are intent upon answering our most serious questions from climate change to poverty, and curing diseases to designing new products, we need to work with people who think differently, not just accurately. And this requires us to take a step back and view performance from a fundamentally different vantage point.’ (p12-13)

I had also observed some school leaders who did or could not fully realise the purpose of their role, which always in my experience, resulted in the school being judged as a failing one by the community, staff or Ofsted. Often these leaders had a single-minded way of leading and ignored the talents that lay before them in their community, rarely was I asked for my opinion or asked to assist in finding solutions. My role was operational and my ambition for myself and that of the community that I served was at risk of becoming dormant. I learned as a headteacher that I was there to listen carefully to the community and the staff and anyone who was there to help make a difference and embrace the diverse skills, ambition and talents of my community[PS4] .

Context

I have been the head of six different primary schools in England, all in different contexts in Devon, Bristol, London and Nottingham. Each community had its own hopes and dreams and a key aspect of my role was to help bridge the gap between their aspirations and their current reality. I have done so, I believe, by keeping my principles and beliefs at the heart of my decision making and, with others, reflecting deeply. Whenever I practised this, the school improved.

During my journey as a leader in primary schools I have had many diverse experiences as each school has been unique as you would anticipate, challenges though have been similar, including a legacy of poor pupil performance. It wasn’t until after my 7th school that I had led to good outcomes for all, including children and staff, that also returned to a failing category within 18 months of me leaving, that I wanted to further investigate and reflect on what it was I was doing to engineer the success that my successor was seemingly not. The following is a mix of stories and acts that I have reflected on that has helped me to begin to understand what I did with others to lead these complex institutions to flourishing hubs of integrity and success.

As a leader, my aim was always to put the wheels back on the ‘failing’ schools and for my successor to keep them on and indeed to change those wheels for even better ones. The schools I inherited always had weaknesses around pupil standards and staff satisfaction; the latter was often defined by staff survey outcomes or staff absence or staff capacity to fully deliver on their roles and responsibilities.

Prior to my arrival in my Devon primary school the headteacher had been in post for more than 20 years. For the last 3 years they had dedicated their time to securing a brand-new inspirational school building for the 120+ local pupils, which included a swimming pool, an amphitheatre and state of the art sustainable building. However, the focus on teaching and learning had waned and consequently pupils’ standards dropped, relationship with the parents severed and some staff were left feeling isolated as they no longer had an 'active listening' leader. Our role as that of a leader according to Ken Robinson is one of ‘climate controller’, which I believe refers to carefully judging and tending to the needs of all aspects of your school and involving others by carefully listening to their possible solutions.

Devon was my first headship, I wanted to be successful. Previously, as the deputy headteacher, I had been leading alongside a headteacher in London at a fierce pace within a dysfunctional leadership team. I describe the team as dysfunctional because despite our diverse leadership experiences and our potential to solve complex problems, rarely did we agree on the solutions to the significant challenges that we were facing. Rarely did we have the time to reflect together without interruption and our roles were reactionary, workloads often impossible to implement, and our daily focus was on responding to the failure, as opposed to being proactive with doable workloads and where success was the daily mantra[PS5] . Consequently, this resulted in high staff turnover, high staff absence and inconsistent and poor pupil standards and engagement, including the highest pupil absence of any school I have worked in. I felt complicit in the system failure and was unable to make a difference then or in the foreseeable future and ultimately resigned.

The headteacher was new to the role and was intent on establishing her understanding of how to interpret her headship. Our relationship had come to an end, as often our solutions were emanating from different positions and our values were not shared.

I recently sought the letter I wrote to this headteacher after not being appointed as the substantive deputy headteacher regardless of seemingly successfully delivering on the roles and responsibilities for the previous three years. The letter illustrates my desire to connect emotionally, to feel valued and appreciated in order to remain at the school, despite me not securing the substantive role. It also illustrates a disconnect between us and the reason for my immediate resignation. Despite us both trying to create spaces to reflect together, to be solution focussed etc. there always seemed to be something that prevented us from doing so. We were unable to communicate effectively with each other. There was a high level of respect for each other and what each other was doing, but we were behaving differently to the same problems and therefore it was time for me to leave[PS6] . I left with a simple toolkit and was on the brink of completing my professional qualification for headship. I knew how to run an organisation and I believed I knew how to further develop the staff pedagogical knowledge.

220 miles away in rural Devon my school had a team of 4 teachers and 120 pupils, aged 3-11. Given the significant challenges as referenced previously, my intention was to reflect on my role and consider what actions and values I wanted to build on to secure best outcomes for all. Initially my behaviours were too rigid, and I was at risk of dividing the community further by using only the tools in my toolkit.

A story

I distinctly remember at my first parents’ evening after six weeks of being the headteacher, one of the parents explained to me that their child did not respond positively to the rigid expectations that they were being faced with. At no point did I consider how my conduct, which was previously successful in London, was unwelcome and unhelpful in Devon[PS7] . I did take this discussion seriously, apologised and sought to more appropriately address their needs and become a more supportive and intuitive leader and teacher.

Dear Headteacher, welcome to the world of leading, you now have no direct line manager looking out for you, what do you do? Go wahey and throw all accountability and responsibilities out of the window or seek others who will inspire and motivate you?

No longer did I have a line manager on site who would observe my every move and ultimately support me to reflect and improve. So, I had to seek other methods that would help me to reflect and become a diverse strategist and thinker. Hence why at strategically planned times I would use surveys to help me better understand how to improve my capacity and that of my team but also how to improve pupils’ standards and outcomes. Other strategies I used to listen carefully to the chatter in the public sphere were:[PS8]

- Network with other professionals and encourage other staff to do the same - it was in this time that Marie Huxtable had discussed with me the need to find spaces to reflect on my practice and offer this opportunity to others. She used case studies to illustrate its impact that inspired me to implement this strategy. Find time away from the school, to record/identify the key issues, identify all possible solutions by networking with others, reading about others’ similar experiences and plan to implement the solutions with others.

- Build in time to reflect on role off site for all teaching and admin staff and then share findings

- Use staff meetings to inspire – using research based methods and staff skills to deliver training– i.e. model the framework of how to deliver a staff meeting using research based theories, model how we practise this method in the school, model what this looked like in the school policy, discuss monitoring systems and dates for action/deadlines of actions and plan for a staff meeting where we would bring our reflections and consider next steps.

- Use performance management as a tool to gauge capacity and ambition and then plan to bridge the gap between the two with the staff member being in much control of how to do that and me or an external professional being the coach.

- Continue delivering on and developing popular school events – like swimming galas, ten tors, school plays, visits to London BBQs etc.

- Speak to staff regularly during quiet moments to gather

- During non-teaching time speak openly to staff about their inspirations were and how I or others could open doors

- Provide safe platforms to listen carefully to parents other than parents evening – make proactive phone calls, provide open days, phone parents immediately there were concerns/times to celebrate undertake home visits.

To gain wider community intelligence[PS9]

Attend

- church services

- PTA meetings

- local events at the library the National Trust properties or similar

- School football and rugby matches

Context

In a small school of only 5 teaching staff, including me, the impact of any newly implemented strategy was easy to monitor, reflect on and celebrate. Staff were becoming clearer on their roles and understood the impact that they were having on the progress of the school.

I helped enhance their capacity to better fulfil their roles. They were a conduit between the home and school and repeatedly championed the success of it. One teacher, who was also a parent and lived in the community, would sensitively inform me of any concerns from parents, governors or the wider community on the horizon. She was my radar and without compromising her position I listened and acted with compassion. This way we avoided a head on collision and the rift between the parents and the school rapidly diminished. She would tell me when to worry and when to act and when to ignore concerns raised. I soon realised when to undertake a proactive phone call and when to undertake a formal meeting. I made myself accessible and soon realised that it was far more beneficial in being proactive than reactive[PS10] . I learned to create listening spaces – times to listen and times to act and then built in further time to discuss the impact of the recent changes. For example, I undertook staff or parent surveys when I had the time to listen carefully and respond appropriately to the findings. When in London, while we did do staff surveys, we never diarised the time to analyse and respond appropriately as a team and so the task became just that, a task, but a meaningless one and nothing changed, and staff felt that their voice was ignored. In truth, it was.

Undoubtedly, I did make mistakes. There were some actions which I did not undertake as they challenged me, which over time became difficult to manage. A sensitive issue ensued, which because of a staff member’s conduct, involved parents, children and staff and led to a milieu of deceit and embarrassment. Specifically, a popular teacher had a sexual affair with one of the parents of a child in their class during the time their spouse worked in the school. If I had had the skills and insight to deal with sooner (the staff member was allegedly bringing the village church school into disrepute, which was a breach of the staff code of conduct), I believe the issues would not have affected the community in the way that they did. This taught me to always address issues with sensitivity and swiftly, even if I had to didn’t have the courage[PS11] or skill set to do so.

The school and the local community became a thriving place where most were aligned with the vision, and people wanted to be a part of the success. Consequently, children thrived, and the school was awarded by Devon County Council and Department for Education as one of the most improved schools in the country. After augmenting my toolkit further, I moved to Bristol to a school in special measures where my skills would grow even further.

I knew I was never going to get it right all the time, in the times I didn’t get it right, like in Devon, I would reflect and learn to be an even better leader[PS12] . I have had limited experience of working in Muslim communities like the one I was now working in Bristol, but I had many diverse experiences of working in ten different educational settings, including two overseas and in primary schools and two in universities so had developed a diverse set of skills alongside a diverse set of people. I could draw on these experiences to secure success where ten headteachers before me had been unable to[PS13] .

During a couple of visits to my new school in Bristol, I was told about the lack of capacity among the staffing and given recommendations by the local authority school improvement team. I aimed to replicate the success of the Devon school. I listened through observing and introducing times to listen and reflect on practices for about 2 months. I didn’t agree to any significant changes, but tried to identify the impact of the practice. Did I have a staff that had the capacity to deliver on this role? Did I have families that were going to be committed to supporting their children? Did I myself have the capacity to do this job successfully? I believe that the answers to all my questions were yes, but not fully yet.

There were four agents that I worked closely with, two of which were from other industries, who helped me position the school on an upward trajectory of success. One was an HR[PS14] agent and the other was a coach[PS15] who had worked in the communication industry, the final agencies that helped were a school improvement officer[PS16] and a local experienced headteacher [PS17] who knew key intelligence details to help me plan strategically and effectively on the ground. They all provided me with the space and questions to explore the diverse solutions. Without these four diverse agencies the success of the school, I believe, would not have been realised[PS18] .

There were some staff that maybe didn't have the capacity to fully deliver on their role yet, but they had the capacity to at least do a significant and important[PS19] job in the school that would contribute towards its success. I devised a plan to help me identify which staff could and which staff would deliver on their roles and responsibilities. This need emerged as a senior member of staff when presented with various solutions would offer the answer of ‘I can’t do that’, I had to identify whether their admission of ‘I can’t do that’, was a defiant declaration, designed to undermine the system and my leadership or whether it was a true position because of barriers they faced. If it was the latter, I was determined that together we would find solutions. There was one incident that I recall which demonstrated that they were defiant, and they wouldn’t follow my expectations and sought to undermine both my leadership and the[PS20] system, hence stalling the success of the school.

I had recently introduced a method to reduce the number of fights between pupils in school; there were anything up to a dozen a day, mainly on the playground. Staff were frustrated that prior to my headship there had been a ‘ban’ on pupil exclusions. They subsequently felt that in order to gain some respect for their role there had to be consequences to pupils’ poor and risky behaviours and so favoured exclusions, so that they could teach, and their class could learn. I agreed with this, but also believed that if children were emotionally supported and intellectually stimulated, they would better understand their roles and responsibilities in school and wouldn’t fight[PS21] . During discussions we also explored our responsibilities to ensure that we were delivering inspiring lessons that engaged the children and motivated them to want to behave better. I had been the headteacher for about 3 months and my first focus was to ensure that the children and staff were safe[PS22] . Neither currently were. Staff and children often presented solutions to problems from a retaliatory and deficit position, which if implemented would create punitive policies that would not improve the culture or pupil engagement. [PS23] There were daily fights between the children. Staff often had to manage[PS24] an upset class and desperate parents etc. After speaking with the children and observing in the classrooms I believed the fighting was because the children and staff were misinterpreting their roles and responsibilities. This was coupled with a lack of accountability that some staff were occasionally guilty of. After significant training on the expectations of the curriculum and how to deliver it with a focus on pupils’ personal development, I designed a clear flow chart of consequences if pupils fought; staff responsibilities were clear and so were pupils’. It included undertaking a full investigation prior to any pupil exclusion being expedited.

Story

I had been at some training for the morning and returned to school to be told three children had been fighting and had been excluded for the remainder of the day. I felt I needed to test the effectiveness of my leadership. I wanted to testify that I had a team that understood their purpose and could keep all safe while I was off site[PS25] . After investigating this fight thoroughly with all witnesses, I deemed that the member of staff responsible for the exclusions had undermined, purposefully or not, the system by not following the new protocol for pupil exclusions. I had noted that there had not been a full investigation into the allegation of a fight and the reasoning for the exclusion. The member responsible for executing the exclusion knew that there had been a fight and knew the children involved but had failed to fully investigate why. If I was to transform a community and gain their trust, they had to see me as a person who led with integrity. Failing to follow through on policy that had been shared with staff and children and hence failing to investigate the fight meant that the children’s voice was not justly heard. With justice as one of my core values I had to be sure that equity had prevailed to secure the success of the school. This in return could mean that if children feel they have no voice, they do not feel valued and may not see themselves as part of the solution. In my experience, if we involve children in the solutions, they are more likely to actively and positively participate[PS26] , and this behaviour becomes contagious and soon becomes the norm. On this occasion, I believed it demonstrated that the member of staff, despite being clear on expectations, believed that the children were subordinate and not that they were victims of neglect. When I spoke with the children and other staff it transpired that a fight had indeed taken place, but if the children’s initial concerns had been addressed, it was unlikely a fight would have ensued. I tried to encourage all staff to be the champion of children’s voice and better deliver on their role and I implemented a range of strategies to help children better understand their roles and responsibilities too. It was going to take time to change a culture. A culture that believed children were subordinate and adults were the only ones with the solutions. I could not have staff undermine my expectations. It was for this reason that I annulled the exclusion and apologised to the children and their parents and asked them to return to school immediately. With regards to the staff member we identified points of development. But moments like these were to be repeated, ongoing misunderstanding or misinterpretation of their expectations of their role had possibly prevented the school from being a successful one sooner.

This type of conduct demonstrated to me that the member of staff could do what was asked of them but wouldn’t. This behaviour from staff in the school was rare. I[PS27] understood that the member of staff wanted to support teachers to deliver on their role – have the capacity to teach, but you cannot align yourself with one group of people and ostracise another, as this will divide the school into a them and us culture believing only one group has the control and solutions. I believe a school should have a rhetoric of we and that together we have the solutions.

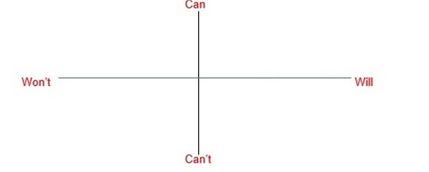

I soon recognised that the can’t and won’t mantra could be opposed with the can and will mantra. I needed staff in the will and can quadrant if the school was to become successful. The more staff I had in there the more I had a capable and judicious team who would secure the school’s success. So, I plotted staff on a Carroll Diagram according to how they delivered on their roles and responsibilities, like the one in the photo - will and can.

‘Will’ was driven by ambition and desire coupled with a clear understanding of delivering on their roles and responsibility. Can was driven by staff capacity and aptitude to be able to deliver on their roles and responsibilities. My aim was to orchestrate all staff into the will and can quadrant, that for me would secure better outcomes for everybody. After plotting everybody on the graph those that fell into the won't and can't category would be supported with a very specific plan to enable them to move toward the will and can quadrant. Those were that were in the will and can quadrant be given leadership tasks[PS28] and opportunities to develop and inspire their own interests in leadership. These tasks included directing, shadowing, coaching, supporting and mentoring those that were in the won't and can't quadrant. there were a range of leadership programmes that all staff were exposed to, these included training from various agents, giving time to develop their leadership skills. Everybody had access to a leadership development programme including me. Staff capacity to deliver on their roles to meet the expectations as set out in the performance management targets and all the other key indicators demonstrated their success.

This model of school improvement was never shared with any staff in the school. I kept confidential records of staff improvement diaries, key conversations, key actions and outcomes, so that not only was I accountable, but they were too and so that we could celebrate the successes that they were responsible for. Each term I plotted staff on the chart according to the progress they were making. Some made progress and then regressed but most progressed. It took a minimum of two years to improve the school and begin to change the culture so that outcomes, in terms of key indicators, were in line with national averages for primary schools. At this school I was rewarded by Bristol City Council for inspiring leadership in a failing school. My leadership was also heralded by Ofsted and the school was judged as good for the first time by Ofsted since its inception in 1992.

All three schools explored here were judged as a failing school within 18 months after my departure.

‘Leaders and governors have an accurate understanding of the school, recognising both its strengths and weaknesses. Their determination to improve pupils’ standards and learning is shared by all staff. Staff responding to inspection questionnaires are unanimously positive.’

Ofsted report excerpt, demonstrating the impact of my leadership skills. I believe the school was so successful because of my diverse leadership experiences and my capacity to understand and manifest what needed to happen.

And Ofsted excerpt after 24 months of leaving the post and passing the headteacher baton on:

Leaders’ self-evaluation is too generous. It is not incisive enough to fully evaluate whether actions are having the intended effect.

Why after clear systems and processes were implemented and outcomes were secure and sustainable, did the schools decline so rapidly? I believe after assimilating my reflections and developing further my knowledge of the science of leadership, that the incoming heads did not always understand and embrace their diverse skills and talents among their workforce and community in order to sustain the improvements and engineer further developments[PS29] . I understood that in order to be successful I needed the help and advice of diverse agencies to help me think outside the box to help me find diverse solutions to complex and diverse problems in addition to recruiting a diverse team.

I went on to lead 4 other schools and continued implementing strategies which led to rapid school improvement. I continued collecting more items for my school improvement toolkit. It wasn’t until I left my sixth school as a leader that I realised that at every school I had left, within 18 months the schools had returned to a failing Ofsted category. Failing to give a good level of education, failing to give the children the opportunities that they deserve, failing to give the children the future that they deserved. Children often start their primary school at 3 years old and leave at 11 years old. 8 years of success is something we should all strive for. Shaping[PS30] the future of that child is a huge responsibility that should be taken seriously, and those leading schools should be accountable. I have often asked myself because even though I am no longer the head of those schools, I still take it seriously that that community relied even if just a little bit on the legacy that I had left. Was my legacy untenable? Was it predicated on mendacities that I managed to hide? Or was it the way that I led the schools and how I developed diverse teams that was not built upon in my absence? I believe the answer is complex; the communities that I led in were complex; addressing the needs of the children was complex; people are complex; therefore, solutions are complex and hence the need for diverse teams to find and follow through on complex solutions[PS31] .

I draw upon the experiences and conclusions from one simple experiment conducted by Francesca Gino and Frank Flynn as cited by Matthew Syed,

…they recruited ninety people and then allocated them to one of two conditions. Half became senders and half became receivers. The receivers were then asked to go to Amazon and come up with a wish list of gifts priced between $10 and $30. Meanwhile the senders were allocated to either choose a gift from the wish list or a unique gift.

The results were emphatic. Recipients, in fact, much preferred gifts from their own list. Why? It hinges upon their perspective blindness. Senders find it difficult to step beyond their own frame of reference. (p22-23)

When teams have diverse experiences, he goes on to state throughout the book, they have a deeper insight into the perspectives of others and together can find solutions to complex problems.

I have little doubt that if I returned to any of those schools that I have left that I would be able to secure an Ofsted judgement of good or better within 18 months or less, if an inspection was to take place. Why do I think this? Because I adopt a diverse style of leadership with my values at the centre and I have done this 6 times before surely that isn’t just fluke but an astute leadership style that has the capacity to identify problems and embrace the skills of available agencies to help solve them[PS32] . My solutions were not just about engineering the best set of results but building diverse teams with diverse and sustainable solutions.

When you keep your principles and beliefs at the heart of your decision making, I believe, and I have demonstrated, that positive and transformational change can take place.

Appendix I- I had been a senior leader in the school for 3 years. I was appointed under a different headteacher who was emotionally intelligent and led the teams with rigour, pace and astuteness. She resigned to take up a role as a consultant and the substantive deputy headteacher became the headteacher. The new headteacher had been incumbent in the school for approximately 8 years. I liked her. I became the deputy headteacher with the same roles and responsibilities I had had for the past 2 years. However, the rigour and emotional intelligence that was once a key feature of the leadership team faded rapidly. This is my letter to the headteacher explaining how I felt excluded by the interview process and how withdrawing my purpose for being in the school left me feeling undervalued and disempowered. From this I learnt 3 things as a leader

- When someone undertakes an internal interim role ensure that you have explored with them during the application and interview stage how you will support them when the role comes to an end and what the options might be – for example I had been doing the role for 3 years and making a significant difference to the lives of children. Naturally I was learning as this was my first senior leadership post, yet my capacity or conduct were never questioned. When I was told in July after the interview that someone else had been appointed, I interpreted this as that I was not good enough for the job I had been doing for 3 years and I became anxious and distraught. All I needed to hear was there was someone else with more experience – you have changed so many things positively and I will make sure that the role you have been doing is protected. In reality, I waited 2 days to be told that I wasn’t appointed, normally in schools you are told on the day and then waited 2 weeks to be told that my roles were up for negotiation. In that time I felt worthless and my ontological identity was questioned.

- When there is a post in the school where internal applicants might apply ensure that it is a just process where equality prevails. Ensure that I have had careful and honest conversations. If I have concerns about the person’s conduct or personality, ensure these are addressed at a different forum.

- Ensure I address any concerns about conduct immediately. – the headteacher would often not address staff conduct or support staff if they were having facing challenges. This resulted in lines of hierarchy often being challenged - staff and parents took it upon themselves to make unsafe and at times belligerent decisions. Parents would often aggressively challenge staff and children’s respectful behavior deteriorated.

July 2010

Dear xx

Thank you and xx for the meeting on Friday afternoon.

There are still some things that I feel need clearing up. I am still unclear as to how you value me as a leader and therefore, I have lost confidence in my ability to lead alongside you at XX.

I fully appreciate the dilemmas that you may have been faced during the advertising, short listing, interviewing and then appointing a new deputy head. I am not blaming anyone for the decisions that have been made, but it is important that you fully understand my thought processes over the last two weeks, which have now led me to the decision that I have lost all confidence in working at Xx

Prior to the post being advertised you had said to me that you were going to give the DHT responsibility for inclusion, but that I did not need to worry; indicating that we would work in partnership to secure my future if I was unsuccessful at interview. I understood the reasons behind this decision and would have happily been committed to this.

It wasn’t until I scrutinized the JD on the eve before the deadline that I questioned what would happen if I didn’t get this post as the majority of the Rs+Rs were mine for the last 3 years. Nowhere did it say that the DHT would work in partnership to lead inclusion and only at one point did it say over time take on the responsibility to … The specific DHT’s Rs+Rs were ‘Line Management of Inclusion Team, Line Management of teaching assistants and to have an overview of provision and its quality by leading on provision management and guidance to support the schools’ inclusive practice.’ It does make sense that if the DHT has responsibility for inclusion that these are their roles, but what about me. I was left feeling worthless.

By Wednesday morning I knew I wasn’t offered the post as a member of staff had accidentally ‘let it out of the bag’. When you told me that evening, I was hoping that you would explain to me what my Rs+Rs were going to be, given that xx would have accepted the post and you would have essentially agreed her Rs+Rs. Naturally I assumed that these were the ones thus described in the job description. At no point did I think that the specific Rs+Rs for the new DHT were up for negotiation, nowhere did it say this in the job description in the advert. In many job descriptions for DHT’s it makes it clear that the Rs+Rs may be generic and negotiable, but the ones for the Xx deputy were very specific. Therefore, my expectation would be that whoever was appointed would have all the Rs+Rs for inclusion.

During that very brief meeting with me on Wednesday you had said that making the decision to not offer me the post was nothing to do with my leadership as you were more than happy with that, but it was all about my ability to balance leadership and management. My thinking soon after was – ok, my leadership is in question and I am not good enough yet. I know I have a lot to learn and I need training and more experience. At this juncture my self esteem was falling like a stone to do that job that I had been doing for 3 years. Unfortunately, my confidence was not restored by you or the governing body as I was not told, and I feel I should have been, what my Rs+Rs were now going to be or that you and the governing body had faith in me as leader. Naturally I felt inadequate and began to question my own self-worth.

I was willing to put my feelings on hold and wait and see what was going to be discussed at the feedback session. The feedback session was an opportunity for both of us to identify the mistakes that I had made during the interview and to possibly discuss my future. The feedback was, I felt, very fair and just. However, my role in the school was still unclear. Now even more confused I wrote the letter explaining that I had lost confidence to do the job. What I needed to hear was ‘I am sorry you have lost confidence, there is no need as you are doing a great job.’ What I was told was ‘I am sorry that you have lost confidence and motivation as a result of the outcome of the interview.’ Thus, confirming my feelings that you thought I wasn’t doing a good enough job and you had no interest in retaining me. Finally, on Friday I thought that we could use this as an opportunity to discuss my future and possibly salvage my self-worth. I asked you how you saw my Rs+Rs evolving in September given that all mine had now been given over to the DHT. This was the first time that I heard that the roles of the DHT were up for negotiation. I was overwhelmed that this had not been explored until now. If I had been told clearly in writing as well as verbally that my Rs+Rs would have been protected, then I would have never felt the need to lose confidence. The meeting was another missed opportunity to restore my confidence in doing the job. I feel that this is a perfectly natural expectation. Affirmations about the execution of my leadership skills should not just emanate from me but should come from you. When I suggested that I leave without notice, given the lack of understanding of my position, I was told was ‘I don’t want to keep anyone here that doesn’t want to be here, but at the moment I can’t give you an answer.’(I do understand the logistics behind the fact that you can’t release me). If I were to stay, I needed to hear something like ‘Paula, you are doing a good job, I am sorry for the misunderstanding. What do we have to do to keep you here?’ I know I was told that I had been a good ‘servant’ to the school, and you apologised for not making my Rs+Rs clear to me. Thank you. But I did not feel that there was an understanding of my position or a desire to capitalise on my skills and talents.

The last thing I wanted was to not enjoy working at Xx or to not feel valued by my line manager. Friday’s meeting for me confirmed the need to move on. If I am told that I am doing something wrong or that I need to improve in an area, I will listen. I know how hard it is to be the bearer of bad news. I will make it as easy for you as possible. I have to because I know it is the only way I can become a better leader, and this is all I have ever wanted. I respect your word.

I hope you are clearer about how I am feeling. It is a learning curve for all. I have been so upset. I want honesty and this is what I got; the very strong message I have had from you and now xx is - Paula you have been good, and we will support your move if we can. The main problems following the appointment were:

- I was never told specifically post advertising of the post that if I wasn’t offered the job then my current roles and responsibilities would be protected – therefore I immediately lost confidence to do the job when I wasn’t offered it

- I was never informed that the inclusion roles of the DHT were up for negotiation

- when I told you, I was losing confidence I wasn’t told I was doing a good job and that you really wanted to keep me in post – I didn’t feel like a valued member of the team

- I was regrettably never asked how I felt about not being offered the post and how I saw my future at xx.

I know I can be verbose, but this is now two weeks’ worth of thinking. I hope that we can both learn from this experience. I would like to work in partnership with you and the team so that the transition can be as smooth as possible.

Thanks for taking the time to read and consider my thoughts and I am sure you have lots to say too.

[PS1]I was doubly disadvantaged – black leaders are rare according to gov data there are only 16 black Caribbean mix headteachers in the England’s 16k primary schools – people over the years had low expectations of me. I never set out to prove them wrong I set out to make a difference and prove me wrong.

[PS2]I am unsure of how I have done this in this piece of writing. I am unsure I have collected enough stories around discourse to show growth – am I demonstrating I get it right in an arrogant way?

[PS3]I have introduced 4 key players but not names what they did to shift a culture and shift my behaviours

[PS4]Have I identified the pressure points in the career fully enough and used LT to illustrate my reflections to improve my practice?

[PS5]Comment on how workloads affect moral and capacity

[PS6]Comment here on disconnect between people and how that creates an energy

[PS7]Comment on the need to adapt to a new expectations but this being outside of my remit

[PS8]Discuss the need to create spaces where we can speak openly without fear without dialectic discusourse

[PS9]Comment on the need to continue keep the boat safe

[PS10]Comment on the need to have a diverse and intelligent team who had a similar agenda but a different skill set

[PS11]Courage in a leader is needed. In a small school where I was rarely 400 m away from the teacher I was scared of rejection. And then of having to face this member of staff frequently without embarrassment.

[PS12]This was like standing on the edge of a precipice. I feared rejection and feared getting it wrong. I had much more to lose. When you are a rare find black and a leader – the only one in Bristol at the time – you have a world watching you and willing you to fail but equally you have a world wanting you to thrive and be successful.

[PS13]Comment on the need to have a diverse team to engineer success

[PS14]To develop a team which understood their legal obligations

[PS15]The need to develop spaces to develop theories and reflect on learning

[PS16]To use experience to provoke and shift thinking and behaviours

[PS17]To use as a sound board and develop and play around with theories without fear or retribution

[PS18]Discuss the need for coaching to be a model of success from ARK research

[PS19]Not only did I stand before the children as a humble servant but before the adults. I was as ambitious for them as they were for themselves. I had to find spaces to listen to over 100 staff as to what their ambition was and set a plan to help them realise this.

[PS20]Comment on how leaders set to undermine to feel validated and important

[PS21]Comment on children being involved in the solutions and the need for a positive behavior model not a defict one.

[PS22]Comment on the need for the brain to feel safety and not feaer

[PS23]Comment here on engagement and punitive strategies

[PS24]This distracted them from their roles nd resposnibilites and children away from feeling safe

[PS25]Test of a leader quote

[PS26]Comment on the need to include children in the solutions

[PS27]Comment on the need for all staff to align with the leaders aims

[PS28]Do I need to case study one of these or bullet point them or outline them further

[PS29]Input comment from MS re diverse skills needed

[PS30]Comment on the need for children to go to a good school

[PS31]What I do know is that by valuing the communities and serving them

[PS32]Comment on being successful