Leading Others in Education

The current pandemic has demanded that some professions redefine how a leader is successful. Behind organisations that have continued to be high performing there has been an enabling culture that has, at times, trailblaze

Being tasked with identifying the functional or dysfunctional aspects of schools I work with, enables me to garner a summary of the arsenal successful ones harness and nurture.

Experiencing crises in schools, and leading or influencing them to sustainable success, I recognise that one of the components was a cognisance of the relationship between staff and high-performance. With people as the main variable within institutions, and believing people are complex, how they behave often determines the organisation’s performance and reputation. If understanding people’s behaviours were simple and then easily changed, surely it would follow that building formulas for successful teams would also be simple. Thompson (2018) states,

In our desperate search for simplicity, people want success to work like a garage door opener, where a four-digit code springs the lock. But culture is not a keypad and people are not doors. Our codes are ever changing in reaction to our environment. p.xv.

Suggesting that people are not easily programmable and solutions that work for one organisation aren’t always easily adapted so that they work for another in a similar context. People respond to their environment. People’s experiences and responses will vary; thus, managing people with different experiences and different responses is complex. As humans we problem solve. Whilst better understanding our behaviours is challenging, we continually try to create formulas or systems that enable a level of certainty of success. This essay will critically evaluate how leaders develop high performance, agile and collaborative cultures in schools. It will also explore the relationships between people and performance and the role that organisational structures play in supporting those relationships and consider some of the consequences of neglecting people’s basic emotional needs.

Teaching is a relational career; this may be why the profession often demands that its staff and stakeholders reflect on the dynamics of effective relationships. Undoubtedly our leadership styles are influenced by our values and a myriad of experiences.

All organisations start with a vision of how they will impact. The culture of an organisation is often born out of the leadership’s values, ethics, behaviours and capacity to achieve its vision. Without positive values that underpin the organisation, it will not thrive for long. Jack Whitehead (2018 cited Academic Assembly, University of Bath, 1988) agrees;

High sounding phrases like ‘values of freedom, truth and democracy’, ‘rational debate’, ‘integrity’, have been used. It is easy to be cynical about these and to dismiss them as hopelessly idealistic, but without ideals and a certain agreement about shared values a community cannot be sustained and will degenerate.

(Location 723/3829)

Effective headship I believe requires, among others, 3 key elements:

- expert pedagogy;

- clarity on how to lead the organisation;

- capacity to manage and influence people.

For all these elements to be sustained and progressed, school leaders should build appropriate structures.

Without a team with the capacity to deliver on its core purpose, to effectively teach, the school will fail. Recruiting the best teachers is not the only mechanism that will develop or sustain success. Schools require a dynamic set of structures, starting with a clear vision and practised values, which attract the best candidates. I have 3 core beliefs regarding recruitment:

- there is a suitable role for every teacher;

- teachers have a responsibility to seek roles that are commensurate with their values and behaviours;

- school leaders have a responsibility to recruit candidates that demonstrate values and behaviours that are commensurate with their vision.

So, in the role becoming vacant, we all have a responsibility in ensuring that the most appropriate person is appointed. From advert to the induction process, the recruitment structures should be wholly aligned with the school’s vision and values. As any deviation from this vision is an unnecessary distraction and could stall the success of the school.

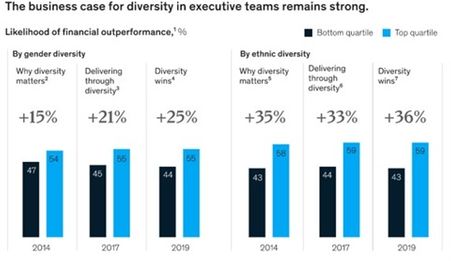

Earlier I mentioned that people are complex. Therefore, solutions to problems with people are complex. So, if schools have structures which enable them to recruit a cognitively diverse set of staff with diverse backgrounds and different reference points, the more likely they are to solve the challenges that all schools are presented with. Syed, (2019) explains,

Homogeneous groups don't just underperform; They do so in predictable ways. When you are surrounded by similar people, you are not just likely to share each other’s blind spots, but to reinforce them. (p24)

Suggesting that by not recruiting cognitively diverse teams, the organisation is more likely to fail.

Syed (2019) reiterates the need for cognitively diverse teams further,

Teams that are diverse in personal experiences tend to have a richer more nuanced understanding of their fellow human beings they have a wider array of perspectives - fewer blind-spots. (p23)

Seemingly, by guarding the organisation’s blind-spots, organisations are more likely to garner success.

As a headteacher in 2012 and in a school that was judged by Ofsted as in special measures, I inherited a team that was cognitively and ethnically diverse, with many staff drawn from the local community and many staff that were new to their roles. With a sense of urgency to succeed, the school had never been judged as good since Ofsted’s inception in 1992, it was essential that I developed structures which allowed me to identify and harness the staff’s wisdom, skills and knowledge, so that we operated more effectively. Despite having a cognitively diverse staff, it soon became apparent that as a leadership team we didn’t have the capability, to corral staff to a united position. Carter (2020) concludes,

Capability = Competency + Capacity (p88).

What I had inherited was people creating a cacophony and using their skills and values to pull the school in different directions. What I needed was a team with different voices, skills and values that were pulling the school in the same direction. With the school having experienced 10 heads in 10 years, the varying structures, values and vision had been lost and confusion had set in. We started a journey under a different set of systems with a focus on long-term gains; we began to build a vision together.

Carter (2020) states,

A focus on short-term quick wins almost always means that leaders make choices that work initially but are unsustainable and, depending on the strategy, and affordable. The most effective leaders and school improvers across the school system lead transformational change that lasts for many years. (p94)

Arguing, investment in the long-term vision better secures sustainability of the success.

All schools have values, ranging from ‘respect’ to ‘pupil first’. How these values are interpreted and practised often determines the success and reputation of the organisation. Whilst the school I inherited practised mainly sound values; it was also staff centric, as demonstrated by:

- inequitable pay awards;

- regular safeguarding or staff conduct breaches;

- part-time roles that suited staff needs rather than children’s;

- above average pupil exclusions.

This imbalanced culture needed to be an area I addressed first.

To test staff capability, before staff changes were considered, I set up a variety of non-negotiable structures where I could use my skills and experiences and gather intelligence to lead the school to success.

These included;

- Reflection and planning opportunities with stakeholders, born wholly out of our understanding of our core purpose and our lived values; by drawing up a manifesto with 1, 3- and 5-year intervals. Plans to bridge the gap between our realistic position and our ambitions were later developed.

- Seeking opportunities with and for staff to develop skills, knowledge and behaviours; with a focus on better understanding pedagogy, purpose of role and how both contributed towards the vision;

- Providing opportunities to be outward facing, networking with and shadowing others locally and globally in schools and in other industries;

- Monitoring the impact of the newly implemented plans against the targets and the accountability systems;

- Creating spaces to reflect on and revise plans as necessary with partners; external (HR, professional survey group and experienced coaches from varying industries) and internal (governors and aspiring/experienced leaders). Giving permission to take calculable risks in a psychologically safe space. Edmondson (1999) describes a psychologically safe space as a,

shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking. (p350)

Developing new cultures and non-negotiable accountability measures often heightens staff anxiety. I wanted to lessen anxiety but needed staff to take risks. According to Syed (2020)

One emphatic finding from psychological research is that humans dislike uncertainty and the sense that we lack control over our lives. When faced by uncertainty we often attempt to regain control by putting our faith in a dominant figurehead who can restore order. (p121)

Implementing those structures, I initially adopted a democratic leadership style, Goleman (2000) describes this style as,

building consensus through participation (p5).

Although a pitfall of this style was potentially repeating the outcome prior to my arrival; where seemingly everyone was listened to and everyone’s wishes were acted upon, leading to confusion and system-wide failure.

Although I felt uncomfortable about deviating from my normal democratic style of leadership to a more coercive one, Goleman (2000) defines this style as

This ‘Do what I say’, approach can be very effective in a turnaround situation. (p85),

the staff centric culture needed to swiftly shift towards a more child or customer first one, if system-wide success was to thrive.

Once our vision, via a manifesto, was established, I was able to switch between leadership styles.

Goleman (2000) concludes,

being able to switch among the authoritative, affiliative, democratic, and coaching styles as conditions dictate creates the best organizational climate and optimizes business performance. (p87)

Implementing the accountability framework with a skeleton of skilled staff nearly broke me. It was a key mechanism I relentlessly made time for, which often resulted with me working an unsustainable 70+-hour weeks. If I was to test the 100 staff’s capability, I needed evidence to drive the next phase. Later I would develop a diverse set of leaders; find time to develop relationships and trust. By plotting staff’s names on a Carroll Diagram against can and can’t and will and won’t headings, Iconcluded a picture of staff’s needs. Those in the quadrant of can and will demonstrated the skills of aspiring leaders and those in the quadrant of can’t and won’t demonstrated a lack of capability. Both groups were afforded a range of support mechanisms, including change in timetables, shadowing opportunities, an external coach, regular check in points and clear expectations of deadlines. My quickly self-improving team added capacity and, after further shadowing experiences and CPD sessions, were able to more effectively lead on aspects of the school improvement plans.

The arrival of a new headteacher is in some ways akin to a pandemic, when both displace a sense a sense of place and order; which may lead to people underperforming. By implementing coaching and designated leadership time off site leaders were able to augment their roles to better suit their styles of leadership and respond to the changing needs of the school. Laker et al., (2020) suggests,

While this may create operational challenges, it enables opportunities to develop task, relational, and cognitive landscapes that bring meaning to work.

Bringing more autonomy to their roles incentivised staff and the school benefitted. Ultimately the culture shifted and better met the community’s needs owing to the actions and agile structures. This was later followed by achieving nationally average, or better, key performance indicators and the school was judged by Ofsted as good two years’ later. Illustrating when both appropriate structures and emotionally intelligent behaviours amalgamate, these can enable and sustain high performance.

The next part of the essay will further explore the relationship between people’s emotional intelligence and performance.

Achieving a vision with people requires leaders to consider and adopt a myriad of effective skills and behaviours. Goleman (1998) believes,

Truly effective leaders are also distinguished by a high degree of emotional intelligence, which includes self- awareness cover self- regulation, motivation empathy and social skill. (p1)

Suggesting that emotional intelligence allows leaders to better understand their community and position them to achieve together. Being self-aware, values-led and cognisant of people’s emotional needs in the community, enables leaders to build the successful frameworks within their institutions.

As a newly appointed assistant headteacher in an amalgamation of an infant and junior school, it was necessary for my headteacher, who I was unfamiliar with, to galvanise the team and corral us to drive the necessary radical and rapid improvements. The headteacher was a values-based leader, exuding and often modelling the expectations she had of everyone and many of the Nolan Principles (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 1995)

- selflessness

- integrity

- objectivity

- accountability

- openness

- honesty

- leadership

This was acknowledged, along with the success of her leadership, during Ofsted’s autumn visit. Under her leadership staff were diligent, knowledgeable, ambitious and dutifully supported the families in the complex community in South East London. Syed (2019) argues,

Prestigious individuals on the other hand are followed out of freely bestowed respect they are in that sense role models.

This means in turn that their generosity towards others is likely to be copied tilting the entire group in a more cooperative direction. (p113-114)

Despite the progress of the school under her empathetic and democratic style of leadership, she lacked some professional grip, particularly with school finance protocols, which was necessary in order to sustain and progress the school. She swiftly left. The staff, and subsequently the school, were plunged into an awry that would take the length of primary aged child’s schooling to fully recover from.Whilst the head modelled emotional intelligence in her leadership and in her address to stakeholders and pupils, what she hadn’t had time to do was develop an effective team that could work together without her direction, and seemingly without her type of emotional intelligence it gained its momentum from.

The deputy headteacher was the first to take on one of the vacant substantive roles and became the headteacher, while all other leaders were temporarily promoted. The values cited in the school’s prospectus and on its walls didn’t change, but the newly practised ones did. This new headteacher isolated themselves, was unable to drive the necessary changes and failed to address the deterioration in staff conduct with rigour and consistency. The lack of emotional intelligence and the capacity to effectively demonstrate the Nolan Principles and create psychologically safe spaces were tangible and a popular topic of discussion by staff.

The previously familiar psychological safe spaces allowed for the pedagogical discourse and leadership capability to be explored without reprisals; essential for us new to leadership roles. If we were to effectively deliver on our core purpose and lead in a complex school, accessing shadowing and coaching opportunities and one to one professional development conversations with line managers, so that we could to evolve as credible leaders, were necessary mechanisms. Scott (2019) cites,

Google employees, analysing more than 250 attributes of 180+ active teams… found that the five key dynamics for successful teams included, psychological safety, Dependability, Structure and Clarity, Meaning, and Impact. But psychological safety was by far the most important of the five dynamics, because it's the foundation of the other four. (p240)

Void of much needed emotional intelligence, including providing psychologically safe spaces, goodwill dwindled because it was neither acknowledged or appreciated, so did the ad hoc and formal conversations and subsequently so did the energy and improvements. Within one year, many teachers, including two senior leaders, left and within 17 months Ofsted judged the school as in special measures.

This story, alongside Kim Scott’s narrative on Google’s survey’s findings, seek to illustrate the influence both an emotionally intelligent and one lacking emotional intelligence can have on relationships and the education, opportunities, wellbeing and safety of those they are responsible for. By consistently expecting and effectively practising the Nolan Principles the school ran smoothly, and without them, it seemingly collapsed.

Expecting all to endorse and practise values, which are based on being loving, just

and ambitious for self and others, should be an inherent aspect of all leaders’

behaviours. The Nolan Principles are integral to the Headteachers’ Standards (Department for Education, 2020)

these form the basis of the ethical standards expected of public office holders.

Not only then is it expected for all school staff to employ these characteristics and behaviours, but that when effectively practised, it is anticipated, the school will journey to greater and sustainable success.

Sometimes being self-aware, being emotionally intelligent and practising the Nolan Principles doesn’t always allow you to influence the outcome needed. I used to referee at Tae Kwon Do sparring competitions. Despite rigorous training, including unconscious biases awareness, it didn’t negate the fact that when refereeing, I was biased towards an opponent I was familiar with, particularly if there wasn’t an obvious winner. I tried to avoid this behaviour, but my emotions influenced my decisions. With punches and kicks sometimes landing in quick succession, it was almost impossible to record them all, so I defaulted to what I thought should be the outcome. I undoubtedly made some inaccurate conclusions, which were heavily weighted by my emotions, as opposed to needing to be influenced by what I witnessed. When faced with two unfamiliar opponents the outcome was rarely swayed by my emotions or biased thoughts. I considered how I could behave differently, to conclude a more just outcome. However, the only variable between the two scenarios was familiarity, and familiarity was saddled with emotions. I was incapable of separating familiarity from emotions.

Whilst I was aware of the limitations my emotions placed on my capacity to be fair, it did not prevent me from lying or exercising a bias, leading to an unfair judgement. The more I tried and focused on being unbiased, the more I was distracted from concentrating on the task in hand.

According to Bhattacharjee (2017)

Our capacity for dishonesty is as fundamental to us as our need to trust others. Which ironically makes us terrible at detecting lies. Being deceitful is woven into our very fabric so much that it would be truthful to say that to lie is human.

When we trace the reason for lying, during my refereeing days one reason was the protection of the reputation of the fighter and the sport, there is often a display of being human and compassionate.

Laker (2020) explained,

the more in tune you are with your emotions, the better placed you are to be able to mitigate them and work with them.

Suggesting, being aware of the ease at which one has the capacity to lie enables us to better understand and demonstrate empathy when we are confronted with someone who is knowingly lying, or we suspect are lying; which I often faced when addressing staff or pupil misconduct.

In conclusion, this essay argues that structures are key to building and sustaining the success all organisations need. There is sometimes a temptation to focus on short-term gains and overlook the importance of long-term mechanisms; the latter will enable the organisation to sustain its success.

Effectively practising positive values underpins the fabric and success of the community or school. The stakeholders and pupils have often chosen the organisation because of the values it practises. If these lived values are different to what is on the school’s display walls or prospectuses, people will notice; leave; and the road to success will be tougher.

I have identified that people are complex. Hence emotional intelligence, understanding and managing behaviours, is needed to build relationships and effective, agile teams.

Finally, I have argued that despite leaders being aware of their limitations, they are not wholly immune from making inaccurate judgments, but by being self-aware, they are more likely to mitigate them and engineer success.

Bibliography

Bhattacharjee, Y., 2017. Why We Lie: The Science Behind Our Deceptive Ways. National Geographic. [online] Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/06/lying-hoax-false-fibs-science/ [Accessed 3 Nov. 2020].

CARTER, S., 2020. LEADING ACADEMY TRUSTS. 1st ed. IPSWICH: JOHN CATT EDUCATIONAL LTD,

Committee on Standards in Public Life, 1995. The Seven Principles of Public Life, also known as The Nolan Principles. London: UK Government.

Department for Education, 2020. Headteachers' Standards. London: UK Government.

Edmondson, A., 1999. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, [online] 44(2), p.350. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2666999 [Accessed 5 Nov. 2020].

Goleman, D., 2000. Leadership That Gets Results. Harvard Business Review, (Harvard Business Review • March–April 2000),

Goleman, D., 1998. What Makes Leader? Harvard Business Review, [online] (3790), p.1. Available from: https://thisisthrive.com/sites/default/files/What-Makes-a-Leader-Daniel-Goleman.pdf [Accessed 5 Nov. 2020].

Laker, B., 2020. How Do Emotions Fit into Work. The Place of Self Awareness.

Laker, B., Patel, C., Budhwar, C. and Malik, A., 2020. How Job Crafting Can Make Work More Satisfying. MIT Sloan Management Review. [online] Available from: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-job-crafting-can-make-work-more-satisfying/?use_credit=0633b7bb0014d1e17f52b06010aff548 [Accessed 6 Nov. 2020].

Scott, K., 2019. Radical Candor. 1st ed. LONDON: MACMILLAN, p.240.

Syed, M., 2019. Rebel ideas. 1st ed. EDINBURGH: JOHN MURRAY, p.23.

Thompson, D., 2018. Hit makers. [London]: Penguin Books, p.xv.

WHITEHEAD, J., 2018. LIVING THEORY RESEARCH AS A WAY OF LIFE. 1st ed. BATH: BROWN DOG Books, location.723.

Meritocracy - the other side of the bright side

Proving You're Right vs Trying to Understand

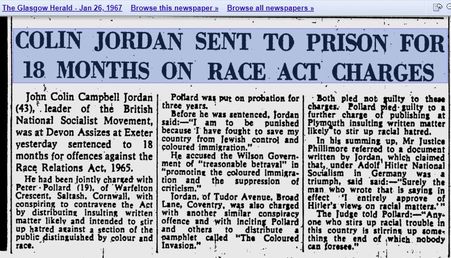

The first prosecution of UK's 1965 Race Relation Act came in 1967.

We have seen enlightenment illustrated so many times, haven’t we? When Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz steps from the black and white threshold into a technicolour world or a make-over with before and after photos or footage, and in all circumstances that are similar, it is as if the mask has been pulled off and the potential and the beauty are revealed. It is this that excites us and has us wanting more. Buying into the ‘if they can do it, I can do it’ mantra.

I work in primary and secondary school improvement and seeking the potential and pulling off that mask is my aim, not just for the benefit of the children in the school, but for the wider community. There are no secrets to a school’s success, although the plethora of popular books written about successful formulas would suggest it is easy to replicate, it isn’t, as the thousands of educational establishments, not in an Ofsted good or outstanding category, illustrate.

British citizens, prior to the industrial revolution, generally did not challenge that there were few opportunities to extricate themselves from the poverty that they were born into, this didn’t prevent many from trying, but a rags to riches story was rare in the 1800 and early 1900’s. Today in the UK we more regularly hear of people extricating themselves from the poverty that they or their parents were born into; often it is the convergence of self-belief, opportunity and a good education that has catapulted them out. I feel privileged to be a part of the education system that enables that to happen, but being part of that system hasn’t come easily for me.

Is Britain a Meritocratic Society for all Ethnicities?

Education in Britain, as already described, is often a vehicle for social mobility, using it to climb up the ladder for an encounter with our vision of enlightenment or our dream job. The meritocratic society dictates that if we work hard, then the opportunity will present itself and we can lull in the vision of success forevermore. The problem with the meritocratic society is that if we believe those that have found a place in their heaven deserve to be there, then we must also accept those at the bottom of society deserve to be there too. The idea of a meritocratic society doesn’t sound so palatable now if we must accept this. We can more easily accept that those that are at the top of society deserve to be there because of their capability and capacity to seek and manage suitable opportunities.

According to the Hofstede Insights, an index of how countries compare culturally, using data-driven analysis pinpoints the role and scope of culture in your organisation’s success Country Comparison - Hofstede Insights (hofstede-insights.com) Britain’s Power Distance (PDI) score is low, suggesting that Britain is

'a society that believes that inequalities amongst people should be minimised. Interestingly is that research shows PDI index lower amongst the higher class in Britain than amongst the working classes.'

Further proposing that those in the higher classes see it as incumbent upon them, and others like them, to actively pursue equality. However, the experiences of many blacks in Britain today would provide a contrary argument that theyor indeed we live in a meritocratic society.

Equalities' data argues the case against Britain being a meritocratic or fair society for those of Black African heritage. Is it true that those of Black African heritage languish at the bottom of society's echelons because they don't work hard or are not capable enough or is it something else that provides the reason why there are so few black leaders and entrepreneur’s in England?

A year before I was born, in 1965, ethnic minorities were undeniably treated to overt and spiteful racism, which was legal. The well-known ‘No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish’ window signs deepened the rejection and fear that many blacks felt. With no legal recourse to challenge the regimes imposed, such as being refused services, access to specific jobs and bed and board, blacks in 1965 Britain often lived an impoverished life. Post the 1965 Race Relations Act many of these racist behaviours, designed to keep blacks at the bottom of society’s ladder, remained legal and it wasn’t until 1968 and 1976 that equality laws that were passed made it illegal to refuse board, service or jobs.

Despite these race relations laws very few prosecutions were made. The 1965 Race Relations act’s first prosecution came in 1967. Demonstrating to me that unlawful racist behaviours continued and were accepted by many, including the police and the justice system, as illustrated by few arrests, charges and prosecutions. For years after the race relation acts were made, those who held the seats of power became less overt and more subversive in the way that they manifested their racist behaviours.

Certainly, because of the context of my birth; colour of my skin; white and Jamaican heritage; the period in which I was born, and the fact that my birth mother was a young unmarried teenager without the total support of her family to keep me, I was admitted into the child care system. If Jamaicans were held in high regard and were respected equally as much as white Europeans and not considered a blight upon the British community, perhaps my birth mother would have been proud to say that I was of Jamaican heritage and would have kept me and I would not have looked at my first born son 20 years later and question how could my birth mother have rejected me, when the love I had for my first born was immediate and intense. That rejection still lives in my belly.

Swapping Overt for Covert

Five decades later, subversive racist practices still triumph in many institutions and some defend their position by citing widely held myths, such as blacks have inherently lower IQ than whites; a mechanism for subjugating blacks in society.

The number of teachers of Black African heritage in English schools is not representative of the number of Black African heritage adults. If schools are microcosms of society, then I believe they should at least have an equitable number of black teachers that is comparable to the number of blacks in society. Of the 22,400 primary schools approximately 40 of them or 0.1% are headed by mixed black leaders; I was, for 10 years, one of them until I moved into school improvement where there are even fewer blacks and mixed black advisors.

In the 2011 Census, out of a total of 1.9 million people (3 per cent of the UK population) who described themselves as black/Caribbean/Afro-Caribbean, of whom 601,700 (0.95 per cent) were Caribbean, along with 1.02 million (1.6 per cent) black Africans and 282,100 (0.45 per cent) other black people. A quarter of minority ethnic people placed themselves in these three categories. More than 615,000 people identified themselves as of mixed white and black descent in the 2011 Census. Most of the community live in the large cities.

By 1984 the Black British population in the UK no longer consisted predominantly of immigrants but was mainly UK-born. https://minorityrights.org/minorities/afro-caribbeans/

So if those of Black African heritage make up approximately 3% of the adult population why is there such a disparity between the national population and the headteacher population of 0.1%? Is the reason why there are so few mixed black African heritage teachers and leaders in schools because they don't work hard or are not capable enough or is it largely because racist systems and structures prevent us sitting at those tables. Moreover is it because there is a lack of opportunities presented to them from secondary school education to leadership promotions?

https://www.repmatters.co.uk/

Representation matters because it reflects what our society values, and if we are to live in and thrive together in a society that allegedly, through its policies and practices, minimises the inequalities, then we should at least seek to remedy the inequalities that blacks face in the job markets.

Even though we may live in a cultural society that believes that inequalities should be minimised there are still institutions and groups that continue to uphold the beliefs that blacks deserve to be at the bottom of society. I have experienced this many times. The stares, the false arrests, the deliberate agitations, the farewells on the first day of a 2-day interview, the lack of invitations to influencing tables.

I was faced with racist barbed wire wherever I walked through my teaching profession; I wear the scars but also the badges of honour of making it through my failed secondary education, university sifting; the first school placements; the interviews; the appointments and later the promotions. It was a tough journey. A story replicated many times by my friends from the global majority, one of whom is of Indian heritage, explained with this one comment which many from the global majority feel, when she said, ‘I came into a profession that I really wanted to be in to make a difference to people like me, but the profession won't let me in.’

Just because I have sat round those tables of influence, it has been fought with a sword in one hand and a willingness to learn and bestubbornly humble in the other . At times I have had to negate my values just to get to that seat. I have had to lower my head and keep my mouth closed. The few times it opened to those who didn't want to listen and embrace difference, it got ousted. I learned to navigate the choppy waters to find many allies and it was here together we enjoyed a place of contentment, excitement, enlightenment and much success. I soon learned to take with me those and learn alongside those where we shared values and visions and where trying to understand was on the daily menu, and to leave those repeatedly telling me they were right and I was wrong while shaking their fists at me, behind their doors of shame.

In 2018, after being appointed in a blind recruitment process, my new line manager told me that they had evidence that there were several members in the community that were racist and that I should ‘be careful’. Although I think this advice was designed to be helpful, it wasn’t. Furthermore, if the leaders felt that community members were indeed racist, I questioned why they hadn’t actively addressed this prior to my arrival as opposed to actively joining me and other like me in the fight for justice and equity. Too many have just looked the other way, they lack courage and they lack insight, but prefer to silently, but doggedly perpetuate the shame, the fear and the inequities of life.

One reason Nazis and Klu Klux Klansmen became acceptable vanguards of racist behaviours was because they enveloped their hatred with scriptures from the Bible. The Bible, the sacred text that millions adopted their beliefs or philosophies from, and which many country’s laws are based was called upon, in their opinions legitimately, to frame hatred and racism. Hiding behind their interpretation of biblical references, allowed racism to thrive for decades.

Legacy of our Behaviours

The legacy of our behaviours and those of our ancestor’s creeps upon us, demanding that we act. I have a belief that when we know better, we do better and if we don't do better when we know better, then we are failing ourselves and our community.

It is no surprise that in 2020 we find ourselves amidst an ecological crisis. According to the BBC website What is climate change? A really simple guide - BBC News

Since the Industrial Revolution began in about 1750, CO2 levels have risen more than 30%.

CO2 increases in the atmosphere is likely to see the surge in natural disasters, including droughts, floods and woodland fires. The activism from across the globe to prevent further ecological disasters is possibly due to a realisation that the sustainability of life is at real risk and we need to act now to minimise this. Our needs and wants must be sacrificed in order to preserve the earth’s natural resources and human and animal life. For years man knowingly neglected the needs of the Earth to preserve their own wealth, status and comfort. Similarly, in Britain, defending racist behaviours and not pursuing race equality was designed to preserve the wealth, status and comfort of whites. Further, defending the patriarchy to the demise of women knowingly, was designed to preserve the wealth, status and comfort of men.

Black Lives Matter Agenda

With the Black Lives Matter agenda protested for in over 60 countries and on all 7 continents, such has been the cry for an end to white privilege and the pursuit of equality. People taking to the streets and to paper, during a dangerous worldwide pandemic, drives the end to unknowingly or knowingly protecting systemic racist mechanisms. No longer can people that sit at the tables of power defend doing nothing to shift the balance of inequality or say they do not know what micro aggressions are or that society values all lives equally. They must try to understand and change their policies and behaviours.

The argument for understanding and embracing the impact of white privilege is on the horizon and rising. Simply put, white privilege for me does not mean that a white person's life is easier than mine, it is simply that the white skin colour has not been the cause of a white person's challenges. I was separated from my birth family because of the colour of my skin. It was difficult to place me into a foster home in 1966 because of the colour of my skin. My white foster mum was spat at, refused entry to places, shunned by friends and family and called racist names because OF THE COLOUR OF MY SKIN. When we understand white privilege, we can understand why some people’s lives are harder than they should be, and we can become more compassionate or considerate and put in place legislation to promote equality.

I will be there with my hands outstretched and I will welcome those that want to change, that want to understand, not to prove themselves right but to try to understand; even those that have lay shaking their fists at me behind their doors of shame, I will listen and I will try to understand and together we will promote equality for all.

As humans we often like and need to feel connected and it is in schools that we have a very important role; ensuring that young people are connected through their similarities, differences, challenges and triumphs, so that they can aspire to carry the torch of equality. If we employ a diverse range of teachers who have a myriad of stories to sell, we will inspire the next generation and we can swap those horror stories that me and my black colleagues have told for stories of hope. When we don't challenge the thinking of decision makers; those in universities; local authorities; justice system; leaders in corporations; governors or trustees; etc, then we risk giving licence to not understanding the challenges others face and in these dark crevices, racism can and will thrive.

We have seen enlightenment illustrated so many times, haven’t we? When Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz steps from the black and white threshold to a technicolour world, it is as if the mask has been pulled off and the potential and the beauty are revealed; let’s run towards that vision of equality for all together, so that the potential and the beauty for all is acknowledged and can thrive.

Education Strategy Today

As a local authority advisor, working with 39 schools, I rarely work strategically across Berkshire’s five other unitary authorities. Despite our contexts, work ethics, vision and values for our schools, being similar, our cultures are very different. Most schools share similar vision and values and mainly work towards the same goal; to provide suitable education for its communities. Yet the primary school culture is often different to the secondary one and the university culture is often different again. A plethora of accountability systems, leadership team structures and opportunities across the phases and authorities have contributed towards different cultures being developed.

Effective organisations will identify and use their values and beliefs as anchors of their decision making. Seemingly, the most effective organisations go beyond developing an agile culture. They also develop one that identifies trends and adapts to the changing needs of their community; one that develops opportunities for the individual and the wider ecosystem.

If we understand that personality manifests itself by a set of behaviours, which is often driven by one’s experiences and values, the same can be said of culture. Culture manifests itself in the behaviours and values of the company or industry or country and can change to suit a need. A need that has often been identified by building capacity to intelligently capture and adapt to trends, while embracing the entrepreneurship and ambitions inherent in its stakeholders.

In this essay, I will consider how cultures evolve and how they can impact on the organisation’s network, and how being aware of some growth and sustainable mechanisms, such as identifying trends and interdependent relationships or characteristics, will secure further success. I will consider whether it is the organisation’s systems or change management processes as opposed to its core mission that is a stronger determiner of its success culture. Moreover, I will explore how trends and data can, when managed intelligently, empower leaders to fulfil their core mission. I will avoid reviewing all the explored mechanisms, instead, focus will be afforded to ones that seem relevant to my previous and current roles and networks.

Our values often determine our behaviours. As a child of the care system for my entire childhood, I knew the influence adults had on a child’s life when the prime carers were unavailable. Driven by a moral purpose to serve and be fulfilled, I entered the teaching profession. Believing in the values of hope, justice and love, I tended to seek challenges in my career, so that I could affect children like me. This is just one example of how our values are inextricably linked to decisions which later become our guiding principles. With these values remaining intact or strengthened during my leadership journey, I have aimed to develop a culture in schools where equity and ambition are drivers of change.

In Mark Carney’s recent series (BBC, 2020) he essentially argues that as a society we value accruing money over people’s welfare and how in turn this can corrupt basic human values. In schools, this can be translated as valuing pupil outcomes over people’s welfare. By putting exam results at the heart of decision making, as opposed to developing a culture that values people’s welfare and ambitions first, we are likely to corrode the altruistic values of many that work in education. With teacher recruitment and retention now integral to many schools’ sustainability strategy, ensuring we prioritise teachers’ welfare is key to determining a positive teaching culture. In a recent survey of 1200 current and former teachers about the challenges within the teaching profession, conducted by UCL 2019, they concluded that “the reason people were dissatisfied with the profession was because of the constant scrutiny, the need to perform and hyper-critical management.” Suggesting that we need to further develop a culture that genuinely values people and their voices and creates success for all, including creating good pupil outcomes, but how?

As a new interim headteacher in a 2-form entry primary school, I inherited 10 new teaching staff, including a whole new leadership team, who were all new to leadership. Creating a culture where everyone could thrive, alongside improving the reputation of the profession, were crucial drivers to my strategy. There had been a culture of high accountability, driven largely by the expectations of the executive MAT leaders, which had seemingly been miscommunicated by the previous headteacher and a culture of fear of failure had reigned. While the standards of teaching and learning were strong, the established teachers were nervous and needed much reassurance to take the necessary risks to continue to adapt their teaching to meet the needs of the children.

Interpreting Hofstede Insights (2020) generated graph to scrutinise cultures, I noticed that

Britain is a Masculine society… A key point of confusion for the foreigner lies in the apparent contradiction between the British culture of modesty and understatement which is at odds with the underlying success driven value system in the culture.

On reflection, whilst culture analyses can feed into biases, this one coalesces with my experiences of working with this teaching team. They had worked in a culture where success of pupil outcomes was the main driver of the decisions, but one in which their welfare and values had been negated. Possibly owing to the teaching staff’s modesty, ten quietly left, and the remaining staff didn’t feel psychologically safe to whistle-blow or address the problems they faced.

Collaboratively we planned a series of actions set against our capacity to identify and manage the associated risks with the aim of changing the culture; from one of fear to one of courage and from one where staff were extrinsically motivated to one of being intrinsically motivated. By embracing the talents and creativity of the teachers I aimed to increase their confidence and capacity.

Within a hierarchal society, where one is considered a subordinate, decreasing confidence is easy, particularly if the subordinates believe their voice yields no power or influence. However, if we shift a hierarchal society to a flatter structure with latitude and longitude conversations being intrinsic in that culture, we can create platforms where everyone’s voice can contribute to the solutions and people’s confidence and self-esteem increases. Habermas’s thesis of the public sphere, where the public’s voice influenced the direction of government policy, was among the first to analyse the changes in the hierarchal power structures. By increasing the opportunity for everyone to have a voice that is actively listened to, we increase confidence and the likelihood of people being intrinsically motivated; a must if we are to retain staff.

Both lesson observations and setting unrealistic attainment targets induced fear in this school. As leaders, we increased staff confidence by flattening the hierarchal structures by adopting these collaborative practices:

a) co-designing lesson observations to focus on development points aligned with the Teaching Standards and their personal and the MAT’s ambitions

b) setting ambitious, but more realistic pupil targets.

Central to further shifting a culture, I implemented a well-rehearsed framework which focussed on the who, what and how, as described by (NESTA, 2018)

From a range of levels (Y axis) in which to observe cultural change and capacity developments and combines these with overall elements (X axis) that should be considered when building (and assessing) innovation capacity.

Y axis; individual, team, organisation and ecosystem, against the X axis; attitudes, abilities, behaviour, discourse, roles, relationships, environment, outputs and ripple effects.

When collaborating on and implementing the framework, from the individual through to the ecosystem (ecosystem, in this case, can be described as the profession), the hierarchal dimensions shifted towards egalitarian ones. As staff regained confidence, the culture changed too, from one of fear to one of courage, thus increasing creativity, entrepreneurship and capacity. As their headteacher for 18 weeks, I was unable to successfully test the effectiveness of the strategy with those outside my organisation. Despite the importance of this mechanism, I felt I was at risk of using surveys to feed my ego, as opposed to providing a useful benchmark to help design the next chapter. Instead, I observed staff and pupil engagement, classroom climates and interactions with parents during my daily gate duties, to gauge the impact of my strategy.

Providing time and spaces to actively listen and respond to the changing climate has always been an essential aspect of school improvement. Being cognisant of the elements that will impact on the profession, such as new market strategies, popular and effective global strategies, enables the leaders to prepare for the future more effectively. I maintain, if you thrive on change, you will thrive in the teaching profession, where change happens regularly as education, new markets and industry are inextricably linked and the success of one is reliant on the other. Referring to Mark Carney (BBC, 2020) again, who offers an insight into tomorrow’s world through the lens of finances, which can be wholly relatable to education “If we value the present much more than the future, then we’re less likely to make the necessary investments today to reduce risk tomorrow.”

By being aware of trends, which I will briefly explore later, and calculating the risks and barriers associated with the possible future changes, ensures that risks are largely mitigated. However, we do have to consider the realistic chances of achieving those predicted outcomes. As too often, “cognitive biases lead us to exaggerate our own performance implications ... and overestimate the impact of the strategy.” (Patel, 2020). Surely exaggerating predicted outcomes, based largely on our evidence is better than no planning? Not necessarily. Whilst no planning is rarely a good idea, if our intended strategy repeatedly does not lead to our predicted outcomes, we are not learning to adjust to affect the necessary changes. By exploring a best-and-worst-case scenario, finding we are comfortable with the risks the worst-case scenario brings, we are more likely to be able to build on the successes of the strategy for the future.

The 2020 A Level results demonstrating our propensity to exaggerate predicted outcomes. Despite a McKinsey report (Bradley et al, 2018) illustrating that only “8% of companies move into the top performing quintile”, often leaders have a veracious appetite and a belief to be ‘top performing’. Attaining a top spot by inflating predictions can put the organisation at risk of corrupting its values, integrity and success.

Though a rigorous process of assessment replaced exams, the grades were based on the evidence the schools had and on what the pupil may have achieved if they had sat their exams. The A level pass rate increased for most subjects, as the data confirms (FFT Education Datalab, 2020) “Grades at A or above increased from 40.4% last year to 53.7% in German, from 19.3% to 35.8% in music, and from 15.9% to 26.6% in design and technology.” While A level outcomes for Mathematics and both English subjects remained largely unchanged, there were some subjects like Modern Foreign Languages, Music, computing and PE that increased by more than 6% each. When the norms for increases in A grades in subjects tends to be around 1%, suggesting that staff inflated, some unintentionally, the A level grade some pupils might have achieved if they had sat the exams.

A relative study corroborates this theory of leaders exaggerating their impact and potential further but adds a rationale (The Telegraph, 2016)

The study, published by the University and College Union, also shows that students are likely to receive more generous estimates on their performance. UCAS chief Mary Curnock Cook said ‘It comes as institutions are now "more flexible" with grade requirements amid intense competition to attract students.

Signifying that market competition can corrupt behaviours and therefore changes our strategy and seemingly distorts the truth. With schools potentially inflating the predicted grades and universities offering ‘flexible’ exam requirements, the credibility of the degree is at risk, which in turn could negatively impact on industry and the health and wealth of the nation.

I was often reticent of deeply reviewing the impact of the strategies on end of year KPIs because the previous year’s outcomes were an indicator of the success of the strategies in that context with those cohorts and those strategies were potentially already obsolete. There were some that impacted positively for all pupils, for example, a long-term strategy to improve pupil engagement. As an experienced headteacher, I found greater value in reviewing the impact of strategies in February and March. As leaders, we often monitored plans by diagnosing and remedying our cold-spots, and redesigning our strategies as necessary, whilst the spring term timing complemented planning future budgets. Moreover, without the pressures of the transition and statutory assessment season, it provided a gateway of time and opportunity, to innovate our change management systems and identify the appropriate staff to lead these new ventures with other networks; that were also not so consumed with end of the academic year events. From these Conjugate, Innovate and Create sessions, we grew a range of initiatives including, overseas study tours, applications for funding or for NPQs/Masters, future proofing strategies and innovative and bespoke curriculums. Although further exploration would be needed to determine the longer-term impact of these initiatives to test their value, the initial outcomes were positive. Using a range of analyses frameworks such as PESTLE and SWOT, we continually evolved our effectiveness, which kept staff’s ambition alive, attracted new staff and fed into the profession’s ecosystem.

The following example seeks to illustrate how intended, deliberate and emergent strategies can be synergised to contribute toward a realised strategy. Using planned strategies are necessary. However, providing spaces to respond to emergent strategies, to effectively impact on education’s changing climate, is also essential. As a headteacher of a school in special measures in an area of high deprivation, void of a senior leadership and shackled by a £250,000 deficit budget, we were unable to address many emerging issues or respond to the changing trends, disadvantaging us further. I needed time to build capacity in the team. Becoming a sponsored academy, the capacity increased, enabling us to apply for ringfenced funding for schools like ours and begin to effectively address, monitor and progress the emerging issues.

Finding the time to monitor the impact of strategy is key to providing the evidence to identify the next steps, which will in turn lead to better planning future strategies. However, at times, we risk over-monitoring, particularly when we do not attain the intended result. This can lead us to either becoming frustrated with the results or worse, repeating the process expecting or manipulating a different answer.

In my role, I worked alongside a new headteacher whose school was in a failing Ofsted category. Keen to measure her impact early on in her role, she commissioned a staff satisfaction survey. She felt it appropriate to be dismissive of the results, believing they were due to the legacy of the previous leader and provided no plans to address the emerging issues. The initial results showed promise of her leadership; staff were hopeful but reserved. Suggesting they did not yet feel wholly psychologically safe to yield their opinions or did not have enough evidence to respond to the questions. Feeling compelled to demonstrate the impact of her leadership on her core mission a few months later, she repeated the staff survey. Expecting the results to illustrate an improving picture, she was surprised and upset to realise that staff were not wholly encouraged by her leadership. This example of the idiom ‘weighing the pig as opposed to feeding the pig’, illustrates that while staff surveys are an effective mechanism in our change management toolkit, providing the right time to implement and space to actively listen and respond to the emerging issues so that we can cultivate the necessary culture, is key to the success of our schools or organisations.

As the culture of both the community and education shifts and the need to continue to be a successful cog in the education ecosystem heightens, it is key that we future-proof our schools and not just focus on improving pupil outcomes, but on how we sustain our capacity to evolve as the trends evolve. Previously I cited Mark Carney about the need to future-proof our organisations to ensure sustainability, so being cognisant of the trends should enable the likelihood of this being realised further. By using the data below, generated by DWP in 2020, I was able to share with colleagues, during recent training modules, that our communities’ parent groups were the most affected by stress since the pandemic started. With most primary school aged parents in the 30-40 bracket, who will also have parents in the 62+ bracket, it provided evidence for colleagues to enable them to discuss and consider emerging strategies to better pre-empt risks. From the smallest action, i.e. touching base more frequently with hard to reach parents, to wider actions which fed into the teaching ecosystem i.e. developing a think tank to provide local and national advice. Teachers and leaders were able to innovate and explore entrepreneurship opportunities with their teams to support their communities further.

Tracking trends today and identifying appropriate ones to respond to enables us to capture and nurture the innovation capabilities within our teams and communities. With several agents providing insight into curriculums, which will nurture the necessary skills for future workforces and communities, including Whole Education and The World Economic Forum, we turn to them for advice; with the latter agent suggesting we need to be mindful of “Eight critical characteristics in learning content and experiences … to define high-quality learning in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” (WEF, 2020) Whilst these characteristics provide a framework for a curriculum, they are essentially no different to England’s National Curriculum that pupils access today. The difference is in the interpretation and the delivery of these frameworks. Both frameworks strongly recommend young people be IT literate and to be aware of the capabilities of IT to engineer and affect change ethically.

Many agents provide support and advice for innovating our IT teaching to enable sustainable growth, IT literacy and connectivity across the globe. According to Luckin (2019)

Research, technology and educational communities (must now) work with Ed-Tech developers in a research rich and evidenced based environment and working in synergy to have more informed developers and more informed educators.

If school leaders embrace opportunities for innovative and trending changes, whilst intelligently offsetting against their capacity and predicted outcomes, they are enabling the sustainability of their schools and of those that they network with.

In conclusion, despite similarities of goals and contexts within the profession, how we interpret our role and apply strategies determines how our cultures evolve. Being mindful of the need to harness wholesome values and behaviours avoids corruption and corrosion across any sector of the teaching ecosystem. Using culture insights can feed biases but can also provide helpful benchmarks for how people behave, thus providing a basis in which to design an appropriate strategy to manage risks.

Systems, such as staff surveys, are essential tools for monitoring effectiveness and to identify emerging issues, so it is essential that we use our integrity and provide time to actively listen and respond to them, to better excite the wider ecosystem of the profession. Moreover, as a strong determiner of the organisation’s success culture, carefully considering how, when and why we implement, and monitor management change tools are worth investing time in.

Finally, leading schools is complex. As schools and industry are inexplicably linked, being cognisant of trends and responding timely and intelligently, enables synergy and progress; as in the case of the Ed-Tech., researchers and education staff programme. This not only takes advantage of trends in IT, but also provides an entrepreneurial opportunity, which excites stakeholders at all levels and helps retain and attract staff.

Bibliography

References

BBC, 2020. Reith Lectures. [podcast] From Moral to Market Sentiments. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000py8t [Accessed 18 Dec. 2020].

Bradley, C., Hirt, M. and Smit, S., 2018. Strategy to Beat the Odds. McKinsey Quarterly, p.7.

Davies, D., 2016. Only One in Six A-level Students is Predicted the Right Grades by Their Teachers. The Telegraph. [online] Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/2016/12/08/one-six-a-level-students-predicted-right-grades-teachers/ [Accessed 2 Jan. 2021].

FFT Education Datalab, 2020. A-Level Results 2020: The main trends in grades and entries. [online] FFT Education Datalab. Available from: https://ffteducationdatalab.org.uk/2020/08/a-level-results-2020-the-main-trends-in-grades-and-entries/ [Accessed 17 Dec. 2020].

Habermas, J., 2010. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press, p.177.

Hofstede Insights, 2020. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/the-uk/. [online] Available from: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/the-uk/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2020].

Luckin, P., 2019. AI and Education: The Reality and the Potential.

NESTA, 2018. Developing an Impact Framework for Cultural Change in Government. [online] NESTA. Available from: https://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/developing-impact-framework-cultural-change-government/ [Accessed 18 Dec. 2020].

UCL Institute of Education (IOE), 2019. Teachers are Leaving the Profession Due to the Nature of Workload, Research Suggests. [online] London: University College London. Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ioe/news/2019/apr/teachers-are-leaving-profession-due-nature-workload-research-suggests [Accessed 18 Dec. 2020].

World Economic Forum, 2020. Schools of the Future Defining New Models of Education for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. [online] Available from: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Schools_of_the_Future_Report_2019.pdf [Accessed 2 Jan. 2021].

Strategic Operations in Education Organisations

Behind each high performing organisation there is a mission and various successfully implemented strategies, usually with an aim of securing improvements and sustainability. However, moving from strategy to implementation may look easy or even possible on the plan, but the reality is often different. This gap (between what science knows and what business does) is wide. Its existence is alarming. (Pink, 2018). If diminishing the gaps between reality and ambitions and the destination of excellence were easy, then surely there would be more than 19% (Ofsted, 2021) of the 24,360 schools judged by Ofsted as outstanding.

Is this because of ‘good being the enemy of great’? (Collins, 2001). As the opening statement of Jim Collins’ best-selling book Good to Great suggests, most people settle for good and this would seemingly translate into most organisations being satisfied with being good, however the organisation or regulatory bodies interpret what good means against their set of metrics. Good performance brings a degree of satisfaction, but aiming for good and not beyond, rarely sets trends or inspires the next generation of leaders and organisations. Furthermore, with limited ambition for being excellent, the organisation, over time, risks getting closer to being satisfactory and failing.

Organisational excellence is not just about setting up a series of checklists of competencies and implementing them, it is also about having; a systematic approach to achieving success; a keen understanding of successful business models; acquiring skills and knowledge of how to adapt to the changing tide and taking appropriate risks that competitors are sometimes adverse to doing. This essay will explore how organisational excellence can be augmented using a series of processes, how some organisations have made the leap from good to great and finally it will explore by affording attention to talent management the organisation’s excellence can be sustainable.

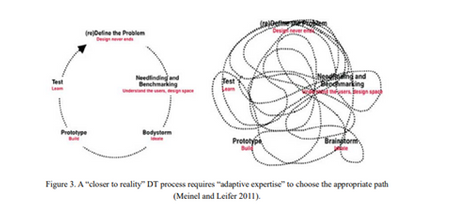

Strategizing to achieve excellence in the organisation is often central to its success. However, understanding the limitations of those strategies must be carefully considered to ensure the aims are realised. US Army General Stanley McChrystal (McChrystal et al., 2015) as cited in (Goodall and Buckingham, 2019) identifies these limitations when planning for the unknown. Despite having the most experienced military agents prepared for action, their operational plans were frequently obsolete against a group of decentralised agile terrorists in Afghanistan, who had no chain of command and could therefore be spontaneous and much more threatening. Whilst plans are necessary for any intervention or action, they only enable leaders to scope the problem, not the solution. (Goodall and Buckingham, 2019). Does this help explain why moving from strategy to implementation is fraught with risks and why organisations sometimes fail to deliver on their targets? Planning against the unknown, using many models, only enables leaders to plan for a predicted world, which can be very different to the real world.

Planning using ASPs, which detail the previous year’s pupil data, should come with a caution. That pupil data tells the story of those pupils and not of the current pupils. Implementing a series of actions, staffing models, curriculum content, timetables, assessment, and reporting techniques, based on the performance of previous cohorts should be fully explored. Scrutinising data and profiles of current pupils, ideally undertaken in the autumn and early spring, to plan curriculums, lessons, timetables, and events is likely to enable schools to adapt with more rigour, agility and intelligence and ultimately improve their predictability of outcomes. Similarly, with Ofsted’s recommendations, many schools are likely to find the recommendations from two years ago are obsolete. Although Ofsted will seek evidence to give them confidence during subsequent visits that their recommendations were addressed, leaders must focus their attention and plans on the challenges that their school is currently facing.

Being aware of the limitations of plans is necessary to attain organisational excellence, but so is creating a culture that allows employees to do and be their best to maximise performance. Essentially, teachers use questioning to seek the experts and the novices within everyone and marry this intelligence with their plethora of skills to achieve set targets. Those leading leaders also need to ask the right questions and create platforms for listening for everyone to better understand how they are a part of the success. Nokia, was once the world’s dominant leader in the technological world.

‘Towards the end of 2009, comparing it with thousands of other companies, McKinseys Organiszational Health Index placed Nokia in the bottom twenty-fifth percentile.’ (Heffernan, 2020) p246-247

Bringing in a new CEO, Siilasmaa, an experienced Microsoft executive with a history of successful change management in the technological world, enabled a significant shift with performance outcomes.

‘Siilasmaa was prepared to go broad. Instead of trying to cut his way to prosperity he cajoled, encouraged, nagged and berated board members and employees to question everything... He conducted what now looks like scenario planning on speed: multiple plans, diverse configurations of what they knew Nokia could look like.’ (Heffernan, 2020) p248

In came a culture that questioned everything and everyone; enabled appropriate risk-taking, and one that encouraged longitudal and latitudal collaborations with competitors, board members and employees not yet in the boardroom. Modelling the possibilities of what the company could do, led Nokia to excellence once again.

Like many journeys to success, there are potential victims. To keep values intact and like (Margetts and Buck, 2018) subscribe to Jim Collins’ belief that the right people are the organisation’s most important asset, then consideration should be given to how people are moved around on the bus, (deployment), and how support is afforded to those that may be taken off the bus, so that each can continue to develop their career.

A two-form entry school with approximately 50% new teaching staff and 100% new SLT tells you something about the previous culture of the school, and despite the reluctance to change things, change was desperately needed. Managing this level of change, when an incoming headteacher was on the periphery, could have caused chaos. With schools at the heart of the communities listening to everyone, so that the baton with suggestions for further change could be passed on, while promoting a culture shift, meant that an intelligent strategy focussed on listening and wholesome values, was in place. With swift appointments made in the last two weeks of the summer term, making sure the right people were on the right bus, so that learning could thrive, was necessary; clearly some people had boarded the wrong bus. Once mission, staff skills and the gap between their reality and ambitions were identified, it was necessary to take some people off the bus. Networking with others, observing HR’s advice ensured that those taken off the bus were able to continue their careers in another setting, or on another bus.

Rarely is the journey to the destination ‘excellence’ on a straight road; it is often a winding one, with many hazards and warning signs. Each of those warning signs needs the leaders’ full attention to avoid the dangers ahead. Anyone being taken off a bus deserves the support, guidance and wisdom of their leaders so they can thrive elsewhere. If leaders support the transition of that member of staff, provided they have skills and behaviours that are worth developing, the brand, the organisation’s reputation, and the ecosystem of the workforce, is likely to be better protected and enhanced.

Responding to the wellbeing of all those in the workforce, even if they are not directly working with the organisation, is everyone’s responsibility. The response to the pandemic, which, owing to the pace of work to address the needs, is creating many of the behavioural risks associated with the last recession of 2008, such as burnout.

(Gerry, 2013) ‘identified via a survey in 2011, that more than two-thirds of respondents said that their employers had taken steps to cut costs as a result of the recession, like hiring freezes, layoffs, cutting work hours, rolling back benefits, requiring unpaid days off, increasing hours. All that increases demands on workers.’

Given this, board members should act to ensure that the people that lead their organisations are equipped to remain resilient, competitive, functional and avoid burnout.

Creating a culture where people’s wellbeing is considered and proactively managed to avoid burnout enables progress of the organisation to continue. Providing forums where leaders and board members can discuss wellbeing needs, tabling it regularly on agendas, affording space and time to reflect and monitor the impact, enables people to feel appreciated. When staff feel appreciated and listened to, they are likely to keep momentum going and go above and beyond for the organisation. (Buck, 2018).

As illustrated by a school which had a strong reputation for tending to the wellbeing of all, during the pandemic it increased the membership of its wellbeing team, which planned to address and update the wellbeing needs of the school and the wider community. It created; a room in school for people to reflect during the day; timetables that enabled staff to better meet the changing needs of their home and school life; forums for parents; food and digital device banks, spaces for governors to proactively communicate with at least one member of staff each half term and risk assessments that placed the safety of all at the heart. Consequently, staff and pupil engagement remained high and most importantly burnout, even though in any pandemic is a risk, was abated.

Creating spaces for the governors or trustees to gain better clarity of what is happening in the classrooms or on the shopfloor is necessary, if challenging. With governors not having an operational role in schools, but being tasked with much accountability for its performance, understanding what is happening in the school means they rely on honest relationships and evidence. Surveys can provide evidence of culture or responses to or impact of changes alongside an opening for governors or trustees to scrutinise more closely and address some of their lines of enquiries that these may flag.

Much research has been carried out to determine that rating others or rating the potential of others and organisations in surveys, is often flawed. The Idiosyncratic Rater Effect, which ultimately reveals that the rating of the person or organisation being rated is not truly driven by who they think the person is they are rating are, but instead by the rater’s idiosyncrasies. (Goodall and Buckingham, 2019) suggest designing a different type of survey, one that avoids the rater rating capacity, but one based on their own preferences or idiosyncrasies.

‘We need to stop asking about others and instead ask about ourselves. Once we designed questions like this, we could then simply ask team leaders…what their experience was like of each team member …or do you always go to this team member when you need extraordinary results?’ (Goodall and Buckingham, 2019) 52.54 Chapter 6

Similarly, (Goodall and Buckingham, 2019) detail that people’s self-serving biases skew accurate feedback. Feedback to help employees garner a better understanding of their next steps to self-improvement is often helpful. However, negative feedback, which often drives the plans and change, is more likely to reflect the feelings the person has about the person they are feeding back to, based on their recent interactions with them, rendering feedback flawed.

‘These biases lead us to believe that your performance, whether good or bad, is due to who you are, your drive or style or evidence, which in turn leads us to the conclusion that if we want to get you to improve your performance we must give you feedback on who you are so that you can increase your drive, refine your style or redouble your efforts to fix a performance problem. We instinctively turned to giving you personal feedback, rather than looking at the external situation you were facing and addressing that.’ (Goodall and Buckingham, 2019) 15.45 chapter 5

Negative feedback can lead to action, which often leads to better outcomes, therefore negative feedback continues to be used to drive plans. Coaching or group coaching may be a better strategy to use to help the coachee to plan their next set of actions. As coaching enables the coachee to see how they can be part of the solution, as opposed to someone pointing out to them that they are part of the problem.

Void of the usual school KPI scrutinies and government accountability body action, the quality of the schools’ health checks during this pandemic is at the mercy of their MATs or their LAs. With a school judged as good in an area of low deprivation the school and good community engagement, it would have been easy for it to hide that it was not coping well. If the LA’s systems and processes were not robust and delivered on swiftly, the outcomes and risks for the community could have been devastating. By insisting that lines of enquiries were followed through and evidence produced, averted this potential disaster. This wasn’t just luck finding out about the challenges the school was facing, but a clear strategic plan to achieve excellence, building intelligent capacity, relationships and systems, meant that the school’s challenges were identified swiftly, additional capacity afforded and risks averted.

‘Great schools are the result of a great delivery, day in, day out...In a school context, great delivery comes from clear systems, processes and support, based on the evidence of what works.’ (Buck, 2018) p18

This floorplan for consistent success isn’t just true for schools, it is true for all organisations and it often starts with recruitment.

Undoubtedly, recruiting teachers has been through a variety of phases. In the primary sector in the southern half of England recruiting teachers to good schools has rarely presented itself as a problem. Overall, 106% of the TSM target was achieved in secondary subjects and 130% in primary. (DfE, 2020).

However, recruiting in rural areas or in areas of high deprivation remains a challenge. 83% of schools found it difficult to recruit heads, with 21% failing to do so. (Slide 109 Carter, David Sir). Equally as challenging, as pointed out during the same lecture, is managing budget; burnout; disengagement and favouritism; workload and short termism, which can all contribute towards making the recruitment and retention problem further. In addition to this challenge is the plethora of accountability or regulatory bodies all wanting evidence that the school is healthy. These include DfE, Ofsted, RSC, MAT CEO's, LA's, STA, TRA, FGBs, auditor's, trustees, pupils and parents. Despite being there to reassure and guide, they can also create tensions. Possibly resulting in the role of the school leader becoming even more difficult to recruit to, particularly because those with ambition for the CEO or headteacher role, witnessing the seemingly impossible challenges that their managers are faced with.

Nevertheless, there are some actions successful organisations take in order to attract, recruit, protect and develop the necessary talent to maintain high standards.

To meet these challenges and sustain a competitive advantage having a Strategic Workforce Plan can help, slide 105, which focusses on:

- Developing capacity to understand and respond to external trends.

- Quality HR teams that support and challenge the status quo.

- Providing clarity on professional development plans and career pathways.

- How feedback and workforce views will be delivered and used.

- How the organisation manages change.

A high-quality HR team operating with intelligence and integrity can help provide the protection that leaders and organisations need. Like a high-quality clerk to the FGB, HR can help quality assure systems and processes and prevent or buffer disasters. Rita Trehan, (BBC 2015) explains why some organisations find themselves in a scandal and the importance of HR.